Posts Tagged ‘prime brokerage’

What constitutes a “full-service” Equities business?

[Part 4 of Equities Context and Content]

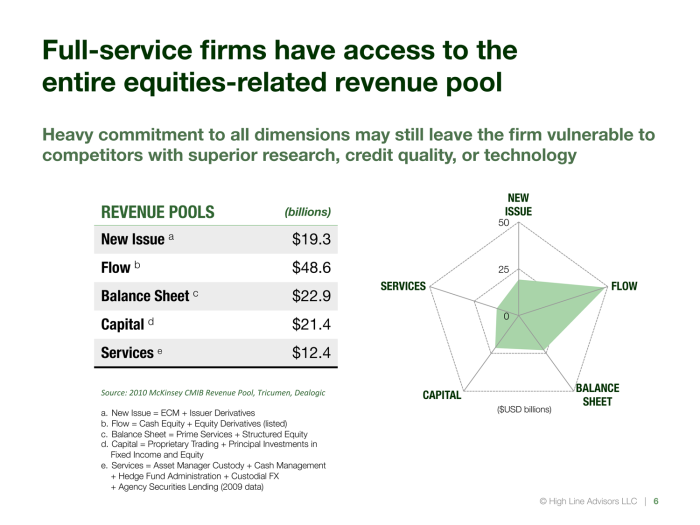

Mature Equities businesses offer a complete array of products and services under the umbrella of Equities. The full-service Equities model incorporates five diversified business lines, each of which has a set of products and services that capture revenue in various forms:

- NEW ISSUE

Origination business based on corporate relationships, resulting in direct underwriting and placement fees and indirect revenues from investor clients seeking to participate in their allocation. Examples include: common and preferred equity, convertible bonds, and private placements. - FLOW

Agency risk transfer business resulting in commissions and the potential for reduced expenses due to internalization. Examples include: “high-touch” and/or electronic order handling in cash equities and listed derivatives. - BALANCE SHEET

Financing businesses resulting in accrual of spreads in excess of cost of funding. Examples include: prime brokerage, securities lending, repo, and OTC derivatives. - CAPITAL

Principal trading businesses, including market-making and client facilitation, resulting in revenues from bid/offer spreads and directional risk-taking. Examples include: underwriting, block trading, aspects of program trading, listed options market-making, and certain proprietary trading strategies. - SERVICES

Low-risk, operationally-intensive agency business resulting in fee income tied to balances or transactions. Examples include: custody, administration, cash and collateral management.

A comprehensive offering allows such firms to compete globally for all client segments and to address the entire available revenue pool. As shown in Table 2, McKinsey estimates the global revenues that may be directly linked to Equities at over $120 billion in 2010.

Figure 2 illustrates the five Equities business lines in a way that circumscribes the revenue pool:

Diversification can reduce earnings volatility and reliance on new issue activity. Of the five dimensions, flow commissions in cash and derivatives account for 39% of the pool, a fact that leads all competing firms to focus on execution capability. With more than twice as much revenue at stake overall, diversified firms not only access the related pools, but may also have an advantage competing for flow.

The capabilities or limitations of a larger firm directly impacts the ability of its Equities business to compete in each of the five dimensions. For example, the firm’s ability to allocate balance sheet and capital to its Equities business allows Equities to offer financing products or to carry inventory in convertible bonds. Similarly, Corporate Banking could drive new issue supply through the Equities business via its capital markets efforts.

Equities Content and Context

We are launching a series and associated white paper entitled “Equities Content and Context: Comparative Business Models Among Banks and Broker-Dealers.”

“Don’t get involved in partial problems, but always take flight to where there is a free view over the whole single great problem, even if this view is still not a clear one.” — Ludwig Wittgenstein

“What you see is what you get.” — Flip Wilson

Article at a Glance

Declining revenues and pending regulation are forcing firms to review their Equities businesses. Competing Equities businesses differ greatly from firm to firm in the breadth of capabilities. As a result, some firms may be unable to access revenue pools that make competitors appear more successful in comparison. A closer look at how a firm’s strengths appeal to specific client segments can reveal why an Equities business is underperforming relative to the market or its peers. An understanding of “boutique” models can provide insight for large banks and smaller broker-dealers alike, whether they are contemplating further investment or a pull-back.

The value of an Equities business to investors is largely dependent on the capabilities of the firm in which it operates. Despite an advantage in breadth of capabilities, large firms that fail to deliver a wide range of products may end up with boutique-like results. Small firms forced to compete on a limited product set can still distinguish themselves in specific market segments.

This article explores the following questions as they relate to managing an Equities business:

- What do investor clients really want?

What are the products, resources, and services that are most valuable to their business? - Why does the firm context matter?

How can other business lines contribute to the success of an Equities franchise? - What constitutes a “full-service” Equities business?

What do the largest, mature Equities businesses offer to clients? What additional revenues do they capture? - How is client value converted into revenue?

How are products positioned as client solutions? - How do Equities businesses align with investors?

Which clients is the firm most likely to attract? - What are the partial or “boutique” Equities business models?

How do firms successfully differentiate? How can a regional or sector-based strategy succeed?

Streamlining Equities

High Line Advisors has published an article entitled Streamlining Equities: Ten Operating Strategies for Competing in Today’s Markets. A PDF of the article is available here.

“Whosoever desires constant success must change his conduct with the times.” — Niccolo Machiavelli

Article at a Glance

Equity sales and trading (“Equities”) is a core business for many banks and broker-dealers, on its own merits and because of its synergies with corporate banking and wealth management. Like all capital markets businesses, Equities under increasing pressure from electronic trading, reduced leverage, increased capital requirements, regulation of over-the-counter derivatives, and limitations on proprietary trading.

New operating conditions call for a leaner operating model to protect revenue and maintain growth, starting with a reevaluation of the product silos that require so many specialists. Profitability also depends on the firm’s ability to deliver resources to clients and capture trades with greater efficiency. Success requires re-thinking the entire legacy organization, looking at new ways to combine or expand roles, and reevaluating the skills that are needed on the team.

These ten initiatives in sales, trading, and operations, can help management streamline the Equities organization for greater top line revenue and increased operating leverage:

- Recast “Research Sales” for delivery of all products and firm resources

- Create “Execution Sales” to maximize trade capture across products

- Rebalance Coverage Assignments to foster team selling for client wallet capture

- Fortify Multi-Product Marketing to maximize product penetration and client wallet share

- Deploy Sector Specialists to generate alpha and raise internal market intelligence

- Implement a Central Risk Desk to consolidate position management and client coverage

- Merge Secured Funding Activity to manage collateral funding and risk

- Centralize Structured Products to eliminate redundancy and internal conflict

- Reengineer Client Integration for speed and control of non-market risks

- Normalize Client Service to eliminate duplicate processes and improve client experience

Collateral Management: Best Practices for Broker-Dealers

High Line Advisors has published an article entitled Collateral Management: Best Practices for Broker-Dealers. A PDF of the article is available here.

col•lat•er•al (noun)

something pledged as security for repayment of a loan, to be forfeited in the event of a default.col•lat•er•al dam•age (noun)

used euphemistically to refer to inadvertent casualties among civilians and destruction in civilian areas in the course of military operations. — Oxford American Dictionary

Article at a Glance

Stand-alone broker-dealers, as well as those operating within banks and bank holding companies, face increasing pressure to minimize costs and balance sheet footprint. Collateral management is a set of processes that optimize the use and funding of securities on the balance sheet. For a broker-dealer, sources of collateral include securities purchased outright, as risk positions or derivatives hedges, and securities borrowed. Additional securities are obtained through rehypothecation of customer assets pledged in principal transactions such as repurchase agreements (repo), margin loans, and over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives. This pool of securities is deployed throughout the trading day. At the close of trading, the remaining securities become collateral in a new set of transactions used to raise the cash needed to carry the positions. Poor collateral management leads to excessive operating costs, and, in the extreme, insolvency.

A disciplined trading operation aims to be “self-funding” by borrowing the cash needed to run the business in the secured funding markets rather than relying on corporate treasury and expensive, unsecured sources such as commercial paper and long-term debt. The funding transaction may be with other customers, dealers, or money market funds via tripartite repo. Careful management of the settlement cycle for various transactions allows a broker-dealer to finance the purchase of a security by simultaneously entering into a repo, loan, or swap on the same security or other collateral.

Many aspects of secured funding and collateral management are common to all trading desks. A centralized and coordinated collateral management function supports the implementation of several best practices and provides transparency for control groups and regulators. Regulation and increased dealings with central counterparty clearing arrangements will soon increase capital and cash requirements imposed on broker-dealers. Even in advance of such changes, customers are placing restrictions on the disposition of their assets and limitations on the access granted to broker-dealers. This trend makes it more critical for dealers to optimize their remaining sources of funding.

Note that the prime brokerage area of a bank or broker-dealer is in the best position to manage the collateral pool as a utility on behalf of the entire global markets trading operation. For more detail, see “The Future of Prime Brokerage,” High Line Advisors LLC, 2010. Figure 1 from the article is provided below. A print-quality PDF may be downloaded from our website here.

Finding New Revenue Opportunities

[part of a series on hedge fund sales coverage]

Existing client revenues may be sustained or even increased in a bull market, but a firm stands a better chance of achieving growth even in bear markets if planning is deliberate and focused on specific opportunities. Fortunately, new revenue opportunities may be found through direct client feedback and some basic marketing.

Sales managers need a minimum amount of useful data that can be acted upon for maximum impact on revenue. A practical client plan must be succinct, easily prepared and easily understood. The planning must be done by the salespeople who know the client best, but supported by data and standards for comparison. Many client planning processes either have too little data or become frustrated in their attempts to collect too much detail. At one extreme, plans based on salesperson intuition are not robust and may be clouded by incentives. At the other extreme, it is impossible to collect precise data from clients who are unwilling to disclose the details of their product utilization or spending to the broker community as a whole. Industry-wide surveys and fee pools may be directionally useful but are not specific enough to optimize the unique relationship between an individual broker and client.

Developing Client Plans

In our experience, a basic but useful client plan consist of three items: an organization chart of the client at the fund level, a budget showing revenue expectation at the product level), and one or more action items required to achieve the budget.

At a minimum, an organization chart for an institutional investor should indicate:

- assets under management (using size as a rough proxy for revenue potential)

- allocation of assets among various investment strategies (using strategy as an indicator of product and resource needs)

- decision makers for each strategy (to identify whom to target for relationship building)

It is best to ask the client directly rather than to rely on assumptions that may be incorrect or incomplete. A map of the client organization can expose any misconceptions regarding their investment activity and lead to the discovery of new revenue opportunities. For example, a convertible bond salesperson may not register that the client also has a distressed equity fund until the salesperson is asked to map the entire client organization. The investment strategies used by the client immediately suggest product utilization, which can be confirmed in subsequent discussions with the client. Existing relationships can provide the introductions needed to open up new trading lines. Simply “connecting the dots” in this way does not require elaborate planning and can yield immediate results.

The next step is to identify potential for revenue improvement. We suggest that detailed knowledge of a client’s wallet are not necessary to manage a successful sales effort. Instead, only a few key pieces of information are needed, and these may be readily extracted from the clients themselves:

- What is the firm’s rank with the client? For each product the client trades (i.e., single stock cash), where does the client currently rank the firm? #1? Top 3? Top 5? First tier? Second tier? Allow the client to define the way they rank their brokers.

- Is it possible for the firm to do better? (i.e., move up in the client’s ranking).

- If so, what would be required? Ask the client what actions it will take for the firm to move up. This can be anything from senior management attention, more outgoing calls from analysts, changing sales coverage, or raising capital. These become the action items.

- What would it be worth to the firm? Ask the client to estimate the incremental revenue opportunity to the firm in each product if the the actions are taken. The sum of historical revenues plus these incremental amounts becomes the client budget.

The questions may be posed by sales people or independent persons or who are not conflicted over critical feedback. It is in the interest of the client to answer these questions, as they seek honest feedback and express a willingness to improve. Once the feedback is provided, an implicit contract is created between the client and the firm that if requirements are met, revenues will follow. It is equally important to find out if the client intends to reduce product trading, or if there is no way for the firm to do better.

When combined with historical revenues, the answers to these questions comprise a business plan for the client: prior revenues (reflected in the initial segmentation) may be adjusted by the amounts indicated by the client as potential increases or expected decreases. The plan must also document the actions or resources needed to achieve the budget. Clients with greater potential for increased revenues may receive higher tiering in the next iteration of client segmentation than suggested by their historical revenues alone.

Marketing From a Product Perspective

While the interview process seeks to uncover opportunities from a client perspective, a product-driven process can yield additional results. Each product area should have its own view of the client base that covers existing clients as well as prospects, and the priorities of the product areas can be represented in the segmentation discussion. A two-pronged analysis that covers the market from both client and product perspectives leads to a more thorough capture of opportunities. The matrix approach also improves governance.

The “product walk-across” report is very powerful for highlighting new revenue opportunities arising from introducing a client to additional products. Some opportunities are suggested by gaps in expected trading patterns: for example, hedge funds that trade ETFs may be candidates to trade index swaps; clients who trade cash and options in the U.S. but cash only in Europe are candidates to trade European options; clients who trade cash electronically may also be candidates to trade options the same way; macro investors who trade futures may be candidates to trade ETFs. Products that are similar or interchangeable may be new to the client or simply traded with another broker.

Product marketing is a process of identifying target clients and managing a concerted effort or “campaign” to introduce the targets to the product. Product marketers can identify candidates from gaps in the multi-product revenue report, and also draw from anecdotal market information and industry surveys that highlight clients who are known to trade in specific products with other brokers.

Clients are more likely to try a new product if it solves a problem for them. The product on its own merits may be undifferentiated, but the broker may be able to add value by identifying an application for the product in the client’s portfolio. Solutions-based marketing creates “demand-pull” which can superior to “product-push” in stimulating or accelerating product utilization. Clients are also more likely to take a meeting on portfolio themes than product presentations. Common thematic campaigns include risk management and hedging, emerging markets access, and tax efficiency.

The opportunities uncovered though product marketing may be cross-referenced and added to the client plans. The product-driven effort may reinforce findings from client interviews, but should also find potential opportunities that the client itself may not have recognized, as well as identifying clients who are not otherwise covered by existing relationships.

Client Segmentation 1: Protecting Revenues

[part of a series on hedge fund sales coverage]

Broker-dealers need economies of scale and operating leverage from their client businesses in order to grow. Covering a large number of clients is therefore an exercise in mass customization: each client must feel well-served as to its individual needs; however, the broker-dealer must find solutions that accommodate multiple clients without increasing costs.

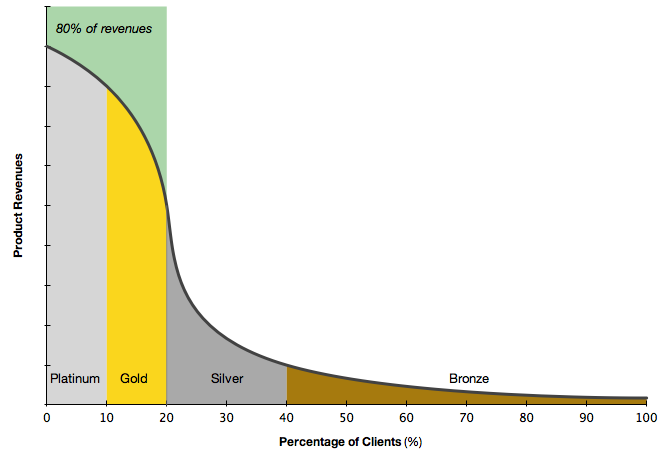

Segmentation is the process of sorting clients into groups with similar characteristics. By grouping clients, product and service bundles may be designed and delivered to the clients that are best served by them. Segmentation can also incorporate a hierarchy that establishes the priority or importance of the client to the business and the corresponding value proposition that the client will receive. A tiered segmentation is particularly useful when allocating scarce resources among the entire client base.

The hierarchy of precious metals shown in Figure 1 is a useful segmentation that is easy for a sales team to remember and act on. Segmentation requires action or it is little more than a sorted list of clients: Clients must be monitored over time and promoted or demoted through the hierarchy to maximize revenues and return on invested resources.

1st Iteration

A good place to begin segmentation is product revenue, so that the business delivers the appropriate resources to existing clients and increases the probability that these revenue streams will continue. Segmentation by historical revenue alone is a defensive approach that protects existing revenues and may induce existing clients to pay more. Once the initial segmentation is established it can be refined into an offensive tool to help capture entirely new clients and sources of revenue.

Product Scope

The first decision to be made is the scope of products included in the revenue analysis. The product revenues define the the client universe by including all active clients who trade the respective products. Inactive and potential clients are not captured at this point but will be added in future iterations of the segmentation.

Products are the payment mechanism for clients. Measurement of revenue in a single product may not be sufficient to capture a client’s entire “wallet” or product utilization and payment patterns. Therefore, the products that comprise as much of any client’s wallet as possible should be included in the analysis. For an institutional equity business, we suggest capturing revenues in the following product “buckets”:

- Cash: single stock

- Cash: programs

- Cash: electronic

- Cash: new issue

- Derivatives: convertible bonds

- Derivatives: OTC options

- Derivatives: listed options

- Derivatives: ETFs

- Derivatives: structured notes

- Derivatives: futures (execution)

- Financing: prime brokerage (margin, clearing, stock loan)

- Financing: OTC total return swaps (other delta-one)

Too much granularity in product definitions can diminish the effectiveness of the analysis. However, it can be useful to distinguish product revenue by currency (to see behavior across regions), to break-down electronic execution to include derivatives, and to separate clearing from margin and stock lending (particularly for listed derivatives). The marketing value of this information becomes obvious once the team begins to analyze client behaviors.

Revenue Reporting

For each product it is useful to collect client-level revenue for the prior full-year, and for the current year-to-date, which may be annualized for comparison. Trailing 12-month revenue may be a more recent full-year measure, but discrete timeframes like calendar years are helpful for observing trends. If capital facilitation in cash or derivatives trading is included in the client value proposition, it is helpful to report top line revenues as well as net revenues after losses from client positions.

The report of product revenues by client can reflect all of this data as changes in revenue over time. For example, client revenues in a specific product that have declined more than 5% below the prior year may be shown in red, while clients showing a run rate greater than 5% above the prior year may be shown in green. A single report that reflects absolute revenues as well as trends leads to more efficient review of how clients are responding to their respective resource allocation.

The report of product revenues by client is sometimes referred to as a “product walk-across,” as in walking across the firm’s products to see a full picture of a client’s activity. Designed to drive the segmentation and resource allocation processes, the report of product revenue by client is a powerful management tool that can be used to review different groups of clients. For example, the report may be used to analyze clients of a certain type or strategy; clients in a particular geographic region; clients assigned to a specific sales person; or, clients targeted by a specific product group. This single report, run against different groups of clients, is the single most important tool for managing a sales force. For the initial cut at segmentation, all clients with revenue attribution are included.

The “80-20 Rule”

In the pool of over 1,500 institutional investors in the U.S., most full-service banks or broker-dealers earn 80% of their top-line revenue from approximately 20% of the largest hedge funds and traditional asset managers, or a total of approximately 300 clients, a manageable number for periodic, meaningful review.

The tail can be very long, consisting of over 1,200 clients that must be continually mined for prospects in which to invest. A key decision remains to either ignore the rest or find a “no-touch” service model, relying on technology rather than humans for service, and allocating only resources that are scalable rather than scarce. A low-cost coverage strategy for smaller clients can provide early access to fast-growing clients, as well as low sensitivity to clients that fail.

For a large, full-service institutional Americas equity business, this framework could result in the following segmentation (shown in figure 2):

- Platinum: the top ten percent of clients, generally “house” accounts, often paying in multiple products or paying so much to one product that they are entitled to firm-wide resources (annual revenues > $10mm)

- Gold: the next ten percent (11th-20th revenue percentile) of clients ($2mm < revenues < $10mm), representing nearly 80% of total revenues for the product universe

- Silver: the next twenty percent of accounts (21st-30th revenue percentile), which may be smaller accounts or those trading in fewer products ($500m < revenues < $2mm)

- Bronze: all remaining clients, often receiving no resources or coverage from scalable “one-touch” or “no-touch” platforms, and allocation of scalable rather than scarce resources

The next step in deploying the client segmentation is to assign the correct value proposition to each segment. The value proposition is an investment in the client, made in the expectation that the client will respond favorably. In some cases, maintaining current revenue is an acceptable outcome, but growth in the business is dependent upon clients responding with additional revenue.

The first iteration of client segmentation and resource allocation based on historical revenues does not reflect any information about new or incremental sources of revenue. A better profile of existing and prospective clients is needed to understand their ability to pay and the factors that influence their behavior. This data can then be used to enrich the process and drive revenue growth.

Hedge Fund Coverage

Our recent post on Team Selling as an alternative to cross-selling prompts a larger series on hedge fund coverage. In future blog posts, we will provide some proven techniques for managing complex institutional investor clients across multiple product areas of a bank or broker-dealer. While these techniques have been applied successfully in a global institutional equity business, they may be extended to fixed income or other multi-product businesses that serve the same client.

UPDATE: High Line Advisors has published an article on this topic. Hedge Fund Coverage: Managing Clients Across Multiple Products is available upon request.

Rules of Prime Brokerage Risk Management

We’ve assembled a list of guiding principals for managing risk in a prime brokerage business, covering the areas where prime brokers are most likely to get into trouble. We encourage the community to contribute to or debate this list. Anonymous contributions may be emailed to feedback@highlineadvisors.com.

- Margin Lending: Don’t finance what you don’t trade. If you don’t have price discovery or can’t orchestrate a liquidation of the collateral, don’t make the loan.

- Margin Lending: Lend against assets, not credit. The ability to value collateral should be a core competency of any prime broker or repo desk, while expertise in credit extension (unsecured lending) is not. Be aware of the boundary between secured and unsecured risk, as lower margin buffers increase credit exposure in extreme (multi-sigma) market events. If you don’t have possession (custody) of the asset, don’t finance it.

- Margin Lending: Finance portfolios, not positions. Diversification of collateral is a significant risk mitigator.

- Margin Lending: Accept everything as collateral, but don’t necessarily lend against it. Cover your tail risk with a lien on anything you can get, but don’t add to the problem by lending against less liquid positions.

- Margin Lending: Be aware (beware) of crowded trades. The liquidity assumptions used to determine margins may be insufficient when like-minded hedge funds simultaneously become sellers of the stock. This goes beyond positions in custody, but those held by other prime brokers as well. Ownership representations are reasonably required.

- Secured Funding: Eliminate arbitrage among similar products. Maintain consistent pricing and contractual terms when borrowing securities or entering into swaps, repos, margin loans, or OTC option combinations with customers.

- Customer Collateral: Accept only cash collateral for derivatives. If non-cash collateral is offered, convert it to cash (via repo), apply only the cash value against the requirement, and charge for the cost of the conversion. Cash debits and credits are the best way to manage margin/collateral requirements across multiple products and legal entities.

- Contractual Terms: Treat clients that do not permit cross-default or cross-collateralization among accounts as if they were as many distinct clients. If you can’t net or offset client obligations, don’t give margin relief for diversification.

- Derivatives Intermediation: Do not provide credit intermediation unless you understand credit risk (again, most prime brokers do not) and charge accordingly. When intermediating derivatives operations, do not inadvertently insulate customers from the credit of their chosen counterparties.

- Funding Sources: Raise cash from collateral, not corporate Treasury. Strive to be self-funding, raising cash lent to customers from securities pledged by customers. Practice “agency” lending (from cash raised from customer collateral) over “principal” lending (from unsecured sources of cash, like commercial paper).

- Term Funding Commitments: Don’t be the lender of last resort unless you understand what it means, want to do it, and get paid properly for it. Only the largest banks with substantial cash positions under the most dire circumstances may be in a position to offer unconditional term funding commitments. Does any broker-dealer qualify?

- Sponsored Access: Have robust controls for high-frequency direct market access, including gateways to enforce trading limits.

“Team Selling” Over “Cross-Selling”

[part of a series on hedge fund sales coverage]

“Cross-selling” initiatives have always struck us as weak efforts to encourage client-centric behavior in essentially product-centric organizations. Incentives often work against the intent, as sales professionals understand their compensation to be driven by revenues in one product line, and annual bonus discussions fail to reinforce broader behavior.

Most broker-dealers are organized by product. The best aspects of product-centric management are risk discipline, operating efficiency, domain expertise, best-of-breed products, and an excellent client experience. Product-centric management works well when there is a 1:1 relationship between clients and products, as was the case historically. Modern asset managers, hedge funds in particular, are not so well-behaved, and may deploy many products or asset classes within a single portfolio. Without a means of communicating horizontally, product-centric organizations can miss overall client activity and related revenue.

What is needed is an approach to balance product discipline with client coverage across multiple products. This requires a “1:many” solution for covering clients and measuring revenue across products. We call the process of coordinating sales coverage of one client across multiple products “Team Selling.” The team is collectively responsible for covering a client, and collectively responsible for maximizing share of the client’s “wallet,” rather than market share for any particular product.

Harvard Business Review recently conducted an interview with Admiral Thad Allen, USCG (Ret.) (ref. “You Have to Lead from Everywhere” by Scott Berinato). Admiral Allen’s comments on crisis management can be applied to the coordination of multiple product specialists in covering complex clients:

“You have to aggregate everybody’s capabilities to achieve a single purpose, taking into account the fact that they have distinct authorities and responsibilities. That’s creating unity of effort rather than unity of command, and it’s a much more complex management challenge.”

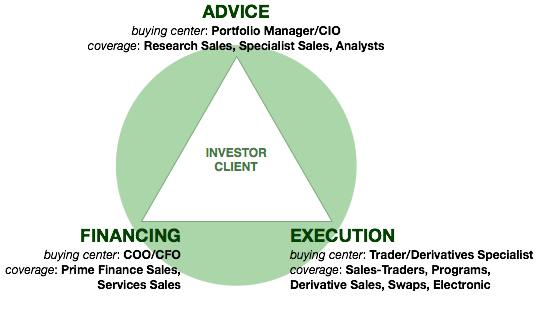

In the context of institutional sales, “unity of effort” implies coordination among separate individuals from different product areas covering the same client (or multiple buying centers at the same client institution), and the “single purpose” they are aiming to achieve is to maximize the profitability of that client.

Using a hedge fund investing in long/short equity as an example, three buying centers can be defined by the investment decision (what to buy), the execution decision (how to buy or express the investment), and the financing decision (how to pay for it). In general, these decisions are made for the fund by different individuals or groups, with the portfolio manager, chief investment officer, or analyst consuming resources to determine what investments to make; the head trader or derivatives specialist deciding how orders are executed, and the chief operating officer or chief finance officer deciding how and where to source financing or borrow stock.

Traditionally, institutional equity sales teams have been comprised of Research Sales professionals covering buy-side analysts and portfolio managers, Sales-Traders and Derivatives Sales people covering buy-side trading desks, and Prime Brokerage or Stock Loan professionals covering the fund’s COO and CFO.

These client-facing professionals tend to be grouped by product, with Research Sales and Sales-Traders associated with cash, Derivatives Sales with derivatives, and Prime Brokerage and Stock Loan sales people associate with those financing products respectively. In a product-centric organization, these sales groups tend to focus on maximizing the revenue in their respective products, without regard for or regular communication with sales people in the other product silos, even if they cover the same institution.

Without breaking the product-centric organization, management can encourage coordination or “unity of effort” across product areas in covering the same client, simply by empowering teams with information on client revenue across all products, (in addition to the traditional reporting of product revenue across all clients). With the common goal of maximizing wallet share and profitability, a client team can work together to make introductions, deliver resources, solve client problems, and fill revenue gaps across the product spectrum.

While easily piloted, the first challenge in team selling is scalability. Scale is achieved when the same team of sales people from different product areas cover the same set of clients. When this occurs, the number of virtual teams can be fewer and their team meetings can be less frequent and more efficient. Rebalancing coverage assignments is difficult but can be rewarding over time: the organization can over a large number of clients as teams operate independently and simultaneously. Team selling is also a compliment to any key account management program, with team leaders corresponding to relationship or account managers. The larger the account, the more senior the team leader. Armed with the right information, anyone in the organization can contribute to or even lead a client team.

Culturally, teams must believe that they will be rewarded for overall increase in profitability of the clients they cover, not only the revenues in the product they are associated with. Client revenue production, product penetration, and profitability can be added to traditional sales metrics in the determination of compensation.

While cross-selling is a product-centric behavior that is by its nature a secondary priority for sales people, team selling encourages client-centric behavior and awareness of the maximum revenue opportunity from each client that the organization covers.

Learning From The Past

“A good scare is worth more to a man than good advice.” — Edgar Watson Howe

“That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

- The self-liquidation of Amaranth Advisors at the end of 2006 was the canary in the coal mine, exposing the difficulty of managing complex customer activity in multiple markets and asset classes, expressed through listed products and OTC contracts in multiple legal entities. Firms had an inadequate picture of aggregate client activity and were uncertain of their contractual rights across the different products. This confusion slowed the movement of cash, creating cracks in the client-broker relationship. Losses at banks were averted solely because of the high degree of liquidity in Amaranth’s portfolio. The crucial question that would haunt banks in the coming months was: what if Amaranth’s remaining positions could not have been sold to raise cash?

- Several hedge funds, most notably those of Bear Stearns Asset Management, began to default on payments in 2007. Unable to raise cash from increasingly illiquid investments, both investors and banks lost money. The defaults drew attention to financing transactions in which the banks did not have sufficient collateral to cover loans they had extended. It is noteworthy that these trades were not governed by margin policy in prime brokerage, but were executed as repurchase agreements in fixed income, in some cases with no haircut or initial margin. Collateralized lending was practiced inconsistently by different divisions of the same firm, some ignoring collateral altogether and venturing into credit extension.

- The collapse and sale of the remainder of Bear Stearns in early 2008 highlighted a different liquidity problem: a case in which customer cash held in prime brokerage accounts (“free credits”) significantly exceeded the firm’s own cash position. Because of this imbalance, Bear Stearns was essentially undermined by its own clients as hedge funds withdrew their cash. Once the customer cash was gone, the firm could not replace it fast enough from secured or unsecured sources of its own. Bear Stearns’ predicament forced the prime brokerage industry to confront some hard truths: Because firms had developed a dependency on customer cash and securities in the management of their own balance sheets, sources of cash and their stability were not fully understood even by corporate treasuries.

- The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September of 2008 exposed the widespread practice of financing an illiquid balance sheet in a decentralized manner with short-term liabilities. Under the assumption that the world was awash in liquidity and ready cash, many firms had neither the systems to manage daily cash balances nor contingencies in the event that short-term funding sources became scarce. The problems of Lehman and its investors were compounded by intra-company transfers and cash trapped in various legal entities.

- The Madoff scandal that broke the following December was in some ways the last straw for asset owners. Already concerned about the health of the banking system and the idiosyncratic risk of fund selection, they lost confidence in the industry’s infrastructure and controls. Banks now contend with demand for greater asset protection and transparency of information.

In summary, the actions suggested by these five events are as follows:

- Aggregate the activities of any one client across all products and legal entities of the bank or broker-dealer

- Establish consistent secured lending guidelines across similar products to ensure liquidity

- Develop transparency of all sources and uses of cash to minimize reliance on unsecured funding [see Collateral Management: Best Practices for Broker-Dealers]

- Match assets and liabilities to term

- Prepare for segregation of customer collateral with operations, reporting, and alternative funding sources